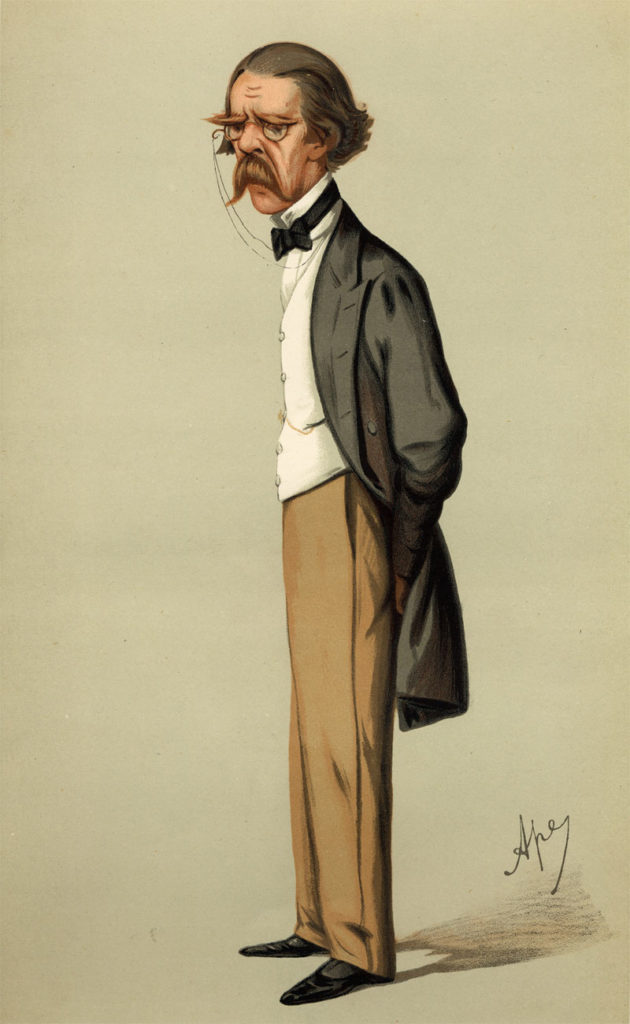

Sir Henry Thompson

Sir Henry Thompson was born and brought up in Framlingham in Suffolk, the son of a Grocer and Tallow Chandler. He became a renowned surgeon with a particular interest in urology, even before the specialty developed. He was the surgeon who finally removed the bladder stone of Leopold, King of the Belgians.

Henry was born on the 6th August 1820. He was educated privately by the local Minister in Framlingham and then by Rev. Andrew Ritchie near Southwold. He made friends with the local doctor and asked his father for permission to pursue a career in medicine; this was refused and he was instructed to follow his father in the business of Tallow Chandler. From 1835 until 1847 he did, gaining a good grounding in the world of business. In 1845, Thompson’s health deteriorated and he returned to Southwold for a rest cure. He continued to pursue his interest in medicine with the local doctor who protested on Thompson’s behalf to his father who eventually relented and gave permission for him to study medicine. After a visit to University College, where he listened to the lectures of Samuel Cooper and Robert Liston, Thompson enrolled as an apprentice to a Croydon General Practitioner and also as a student at University College in 1847; he was aged twenty seven.

Thompson’s success started rapidly at medical school. In his first year he came joint first place in Anatomy, in his second he won the Gold Medal in Anatomy and the Silver Medal in Chemistry. These were followed by the Gold Medal for Pathology and second place for Surgery. In June 1850 he was elected House Surgeon and in October passed the examination at The Royal College of Surgeons. In 1851, he gained his MB BS coming second place with honours in medicine and surgery and winning a Gold Medal in both. He rented a house at 16 Wimpole Street in London, put up his brass plaque and set up in practice.

Henry Thompson was winner of two Jacksonian prizes at the Royal College of Surgeons, the first on urethral stricture, publishing his work in 1852, the same year as qualifying as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. The second Jacksonian prize was on diseases of the prostate and in 1862 gave the Lettsomian lectures on the subject of “Practical Lithotomy and Lithotrity”. Clearly, Thompson had a particular interest in genito-urinary diseases. Thompson was particularly adept at passing instruments urethrally and championed per-urethral lithotrity against open stone surgery. In 1847, Thompson travelled to France to be elected as a member of the Societe de la Chirurgie and at that time was taught the technique of lithotrity by Jean Civiale himself.

His public fame stemmed from his successful lithotrity of Leopold, King of the Belgians’ bladder stone in 1863. Thompson was called in for his opinion after both Civiale and Langenbeck had failed to rid the king of his stone. Thompson had a set of new instruments made for the king and took with him Mr Joseph Clover, as his Chloroform Clerk (anaesthetist) to apply the anaesthetic. On June 6 he injected the bladder with 2 oz of water, and introducing a sound felt something hard. He passed a lithotrite caught the stone by its short diameter and crushed it twice. Four days later the operation was repeated. For his services Thompson was paid £3,000 and was knighted by Queen Victoria (Leopold was her favourite uncle!). One aspect of his procedure that probably influenced his success was the new set of instruments. If not sterile, they were at least clean and unused.

Thompson was later called upon to treat the bladder stone of Napoleon III of France. He passed his lithotrite on 2nd January 1873 and again on the 6th. Unfortunately the Emperor died on the 9th of chronic obstructive uropathy and urosepsis. Although this was unsuccessful Thompson’s reputation remained intact. The image of Sir Henry Thompson above is from the popular magazine, Vanity Fair, one of a series of cartoons of ‘Men of the Day’, indicating Thompson’s fame.

Sir Henry Thompson however, was much more than a urologist or even a surgeon. Like many Victorian gentleman, his interests were broad and varied and ranged from poultry farming, painting and astronomy to the collecting of rare porcelain. Not just a gentleman amateur, he excelled at all of his hobbies becoming a renowned expert in them all. Even at the age of 81, Thompson’s interest in new pursuits had not diminished. In 1901 he bought a Daimler 6.5 HP motorcar, writing a series of letters to The Times newspaper in support of the new invention and publishing a book, “The Motor Car. Its nature, use and management”, in 1902 explaining the “anatomy and physiology” of his car.

Sir Henry Thompson died in 1904 at the age of 84. Thompson, although like all his contemporaries, a general surgeon, devoted the majority of his practice to diseases of the genito-urinary tract. Often called the first British Urologist, furthermore, he subspecialised in diseases of the lower urinary tract and today he would doubtless be an endourologist.