Mr. J.C. Goddard | 19 Oct 2022

At some point after 1853 and prior to 1865 a Desormeaux endoscope, or one very similar, was acquired by Francis Cruise (1834 – 1912) a Dublin surgeon. Cruise was disappointed with its poor illumination and soon abandoned it. However, some time later he returned to the idea of endoscopy and planned to improve on Desormeaux’s design. According to Cruise, he had found the prospect of viewing the interior of the body and its cavities in a living subject fascinating since his student days. Certainly the Desormeaux endoscope had been first introduced during Cruise’s time at Trinity. He also made it clear he had tried a Desormeaux type endoscope some years prior to presenting his own. On March 15th 1865 Francis Richard Cruise presented his version of the endoscope to the Medical Society of the King and Queen’s College of Physicians of Dublin.

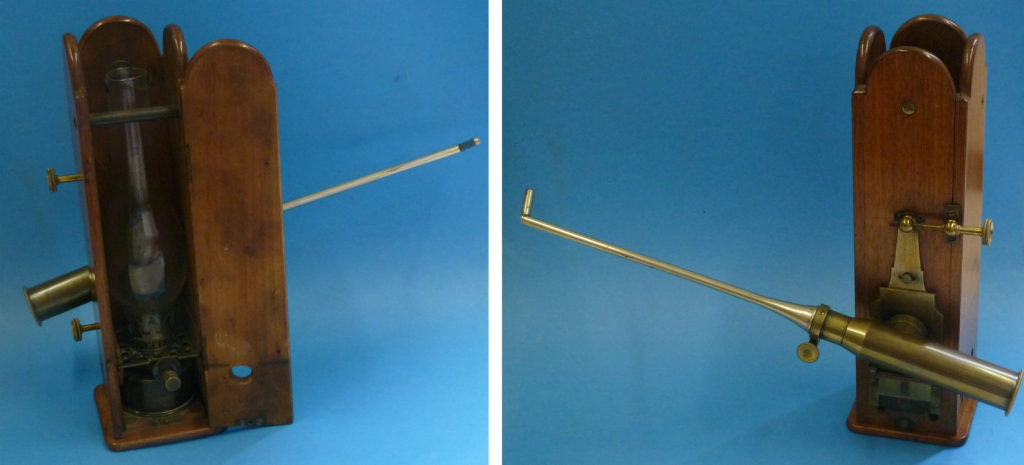

Francis Cruise’s main criticism of the Desormeaux endoscope was the dearth of light projected into the body cavity. Although Cruise used his endoscope to look into various body cavities it appears that the urethra was the area most frequently examined. Clearly, in order to examine the length of the male urethra, a tube or speculum needs to be long and narrow. Thus, in order for light to penetrate to the end of this long tube the source had to be very bright indeed and Cruise acknowledged this to be “the grand difficulty” of endoscopy. Cruise, after some experimentation found that the thin edge of a flat petroleum lamp flame was the brightest light source available. The light intensity was further improved by the addition of camphor to the petroleum fuel. He added ten grains of camphor to each fluid ounce of petroleum. Also, a tall glass chimney helped draw and steady the flame. A mixture of burning petrol and camphor however creates a lot of heat. In order to make his instrument practical to hold Cruise encased it in a mahogany box; mahogany is a good insulator. Interestingly he felt his burning petrol and camphor mix was a safe option. He was however comparing it with burning magnesium wire and limelight (where a jet of oxyhydrogen ignites quicklime).

Cruise next had to accurately focus his narrow bean of bright light. The height of the flame could be adjusted (as with any spirit lamp) so its edge was directly opposite a condensing lens that focussed it onto a reflecting mirror at 45 degrees. The lens could also be slightly adjusted up and down and forwards and backwards by the aid of brass rack and pinion and tangent screws. The reflecting mirror had a small hole in it to allow the user to see through it as the light was shone through the endoscope body and down the speculum into the body cavity.

To protect the user’s eyes from the glare the interior of the scope was painted matt black and a perforated diaphragm (or iris) sat between the mirror and the eyepiece. For those who were long or shortsighted, an extra corrective lens could be put into the eyepiece. Cruise felt that his light was not only brighter but allowed him to distinguish colours better than Desormeaux’s rounder gasogene flame. He likened Desormeaux’s poorer light to twilight as compared to his brighter daylight.

Using the Cruise Endoscope

Prior to using the Cruise endoscope, the fuel is topped up, the wick is trimmed and the lamp lit. The endoscope light is carefully adjusted, the flame height raised or lowered using the small wheel on the side of the instrument. The light beam is then focussed using the two brass adjusting screws.

The greased urethral speculum (with its blind obturator in position) is passed into the urethra (as yet unattached to the endoscope). Once the tube is against the sphincter the surgeon places a greased finger into the rectum to guide it into the prostatic urethra. The obturator is withdrawn and the lit and focussed endoscope is attached. The endoscope is held in the left hand and raised to the user’s eye to look through. The scope is then slowly withdrawn throughout the length of the urethra with the surgeon carefully observing the illuminated urethral mucosa as it comes into view. No air or fluid is used to distend the urethra it has to be examined as it falls into view at the end of the illuminated tube as it is slowly extracted.

In order to carry out a cystoscopy, the bladder has to be partially filled with clear fluid. The cystoscope attachment is a closed tube with a small glass window at the end. Cruise was able to see cystitis, stones, trabeculations and bladder tumours. On 4th April 1865 his friend and colleague (and former teacher) Dr Robert McDonnell set Cruise a little test. Into the bladder of a fresh cadaver (via a suprapubic incision) he placed three objects. Cruise correctly identified a brass screw, a bullet and a piece of plaster of Paris with his endoscope.

Images: The Cruise Endoscope in the Museum of Health and Medicine, University of Manchester, UK. Private photographs, used with permission.